INTRODUCTION:

In July 2004, music journalist Richard Skanse captured a moment in time that now feels quietly historic. His long, thoughtful piece on Todd Snider did more than review an album — it documented the inner life of a songwriter who had already lived several musical lifetimes before most artists ever find their footing.

At 37, Todd Snider was not old by industry standards, yet he was already carrying the emotional mileage of someone who had slept on countless couches, crossed the country more times than he could remember, and collected stories the way others collect records. In the opening track of East Nashville Skyline, “Age Like Wine,” Snider jokingly refers to himself as worn and fading — but beneath the humor lies a sharp self-awareness. His songs compress decades of movement, mistakes, friendships, and stubborn independence into moments that rarely last more than a few minutes.

What Skanse understood — and what many listeners were just beginning to realize — was that Todd Snider’s restlessness was not a flaw. It was the engine. Long before he became a touring troubadour, Snider had already lived as a drifter, first by circumstance, then by choice. Gathering stories, reshaping them, and turning them into songs was not an artistic strategy; it was survival.

Inspired early on by Jerry Jeff Walker, Snider briefly brushed against Texas before moving on — not because Texas failed him, but because standing still never suited him. His career only began to take recognizable shape in Memphis and Atlanta, leading to his 1994 debut Songs for the Daily Planet. That album introduced listeners to “Talkin’ Seattle Grunge Rock Blues” and “Alright Guy,” a song that would later be covered by artists like Gary Allan and nearly by Garth Brooks. Even then, Snider was writing for the overlooked — the awkward, the unlucky, the quietly resilient.

Despite label changes, setbacks, and industry confusion, each subsequent release showed growth. From the raw rock edge of Viva Satellite to the honesty of Near Truths and Hotel Rooms Live, Snider was becoming sharper, braver, and more himself. Along the way, he earned the respect of songwriters who mattered — Billy Joe Shaver, Jerry Jeff Walker, Jimmy Buffett, and John Prine, whose Oh Boy Records would later become Snider’s creative home.

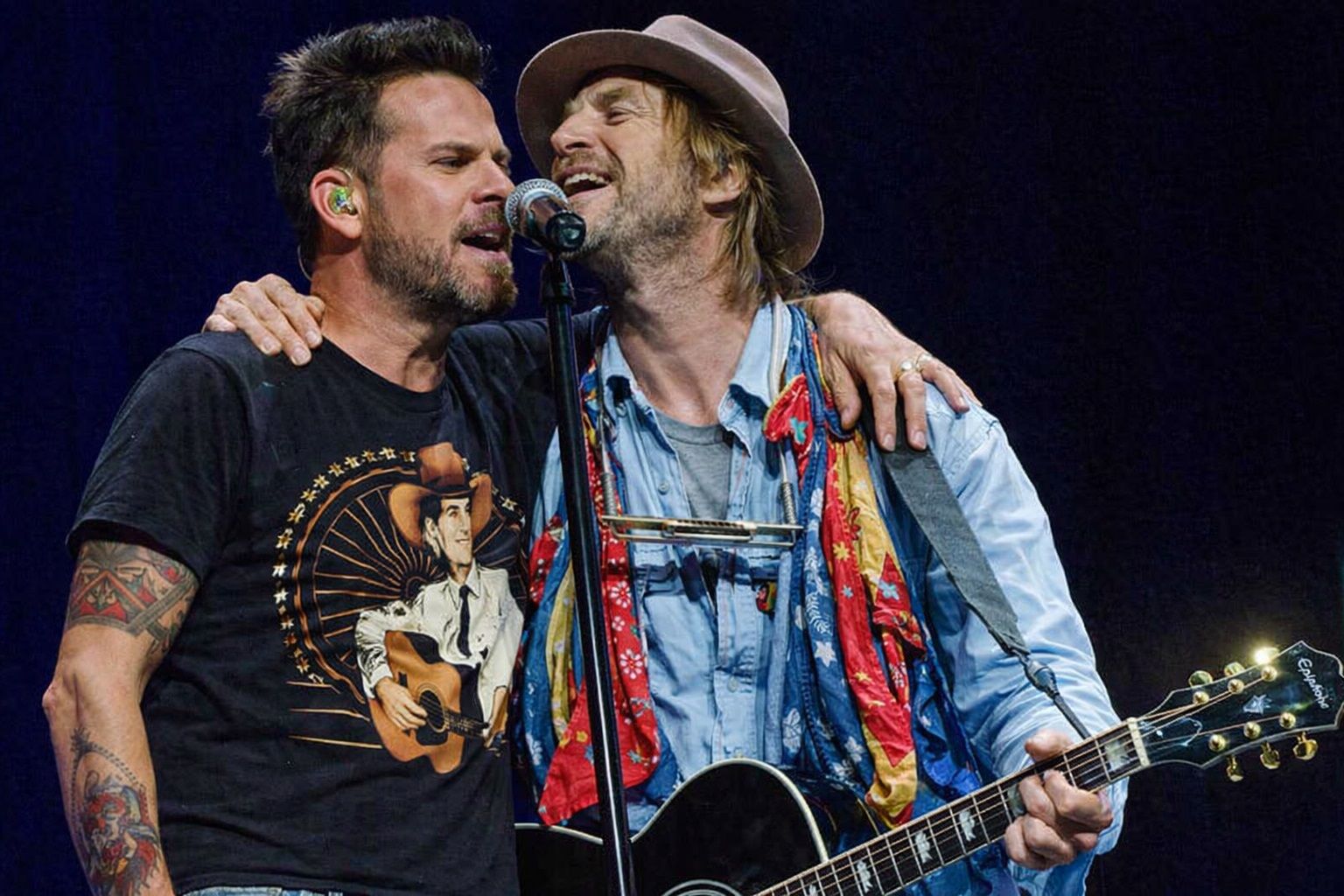

What truly set Todd Snider apart, as Skanse noted, was not just his songwriting but his presence. Fans and fellow musicians alike described him as one of the greatest live performers they had ever seen — a man with nothing but a guitar who could hold a room without effort. His memory, too, was astonishing. He remembered interviews, rooms, passing comments, and offhand jokes years later, not as trivia but as part of an ongoing human connection.

East Nashville Skyline marked a turning point. For the first time, Snider was consciously shaping a conceptual album — a portrait of a neighborhood, a community, and a shared emotional weight following the death of a beloved local figure. The record became a quiet meditation on grief, place, and healing, even if Snider himself admitted he didn’t fully understand it yet.

Perhaps that uncertainty is the key. Todd Snider never claimed to have answers. He trusted humor more than anger, stories more than sermons, and honesty more than polish. His songs spoke plainly, laughed at themselves, and carried a humility that refused to posture.

Looking back, Richard Skanse – ngày 1 tháng 7 năm 2004 did not just document a musician promoting an album. He captured an artist in motion — flawed, thoughtful, funny, and deeply human. And in doing so, he preserved a snapshot of a songwriter who would continue to age not like wine, but like truth: slower, deeper, and impossible to rush.